Rather than banning the consumption and trade of wildlife, we should be conserving our forests and recognizing the vital contribution of wild species to global food security, particularly those of indigenous peoples, who make up 6.2% of the world’s population.

Indigenous lands hold 80% of the world’s biodiversity. With an enormous wealth of experience accumulated through many generations, indigenous peoples are best at managing lands, forests and other natural resources. Many studies have shown that traditional governance of land is more effective at conservation than state-led conservation initiatives.

Indigenous people and biodiversity

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), indigenous peoples represent over 19% of the world’s extreme poor. However, they are also very resilient as their age-old traditional knowledge enables them to survive through food shortages, forced resettlements, and disease outbreaks, as well as adverse climate impacts.

Indigenous groups play a vital role in the protection and conservation of biodiversity and are regarded as forest stewards around the world. Coming from a long history of traditional protection, many indigenous communities in Southeast Asia, such as the Karen in Myanmar, the Ngata Toro in Indonesia, and the Igorot in the Philippines, imposed voluntary self-isolation and locked down their communities from outsiders to avoid being infected by COVID-19.

Government lockdowns in several countries lead to restrictions on the transportation of agricultural goods to indigenous territories, affecting food access and the trade of non-timber forest products indigenous people sell at urban markets. With the subsequent income reductions and food shortages, many communities have turned to nearby forests as a backup, where familiar ecosystems provide them with free, fresh and safe food.

The link between indigenous food and global health

Wild foods are undomesticated edible plants, fungi and animals that provide sustenance and nutrition, as well as income. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that wild food contributes to the diets of one billion people, significantly contributing to food security for people in tropical forests. Studies show that game and fish provide 20% of the protein consumed in at least 62 developing countries. In Svay Rieng, Cambodia, wild fish caught in the paddies make up as much as 70% of the community’s protein intake. Another study of twelve indigenous communities from different regions of the world showed that traditional food species can provide up to 96% of their total dietary energy.

Micronutrient-rich foods from forests, coupled with agroforestry harvests, ensure that forest communities have a diverse source of nutrients, micronutrients and vitamins not found in processed food. A study by Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Indonesia revealed that in rural areas, children living near forests are less malnourished than those farther away.

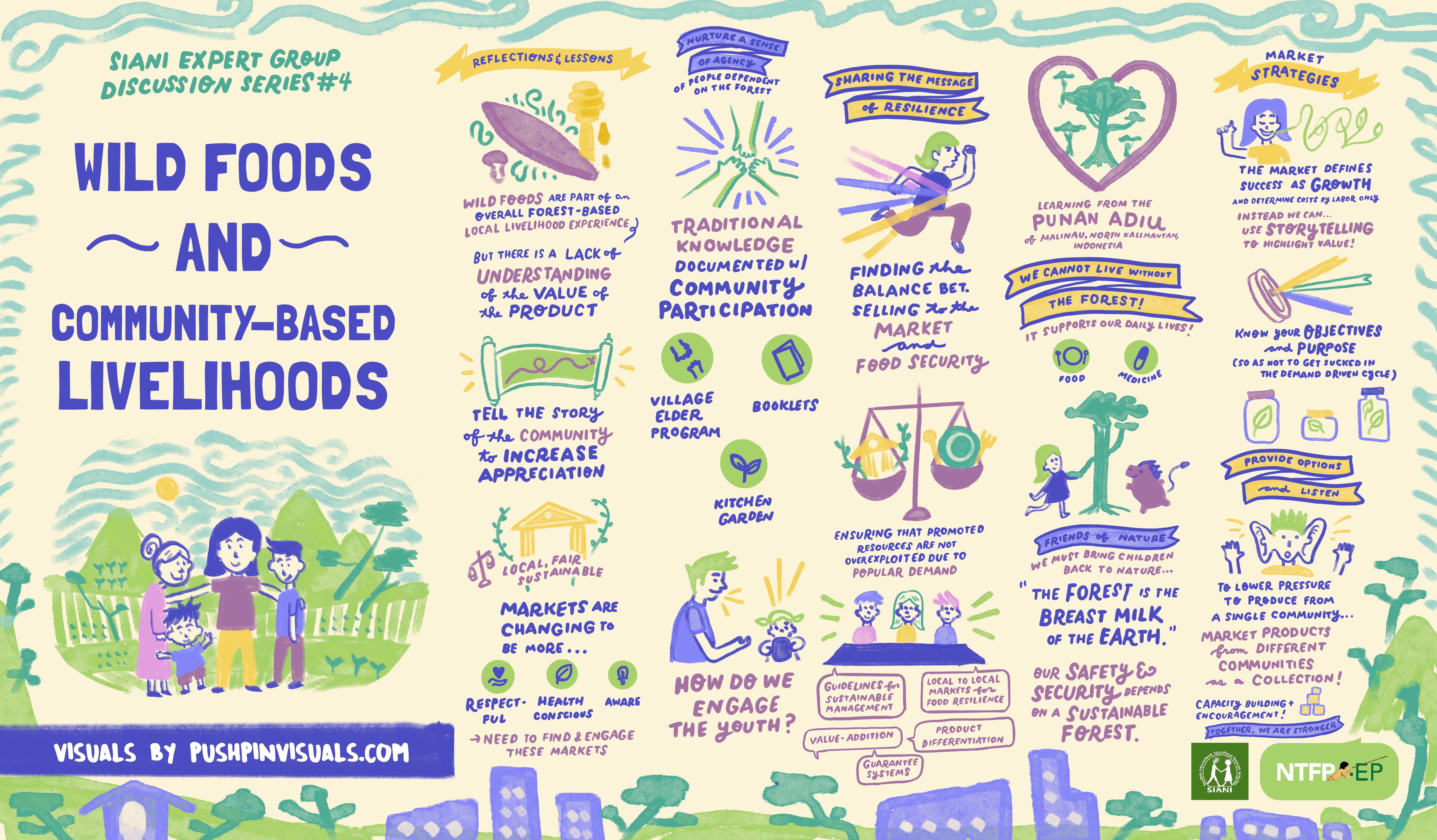

However, apart from nutrition and income, wild foods are linked to indigenous cultural identity, with traditional skills and knowledge on harvesting and hunting passed from generation to generation. So, when the youth doesn’t gain traditional ecological knowledge from their elders it leads to cultural disintegration and threatens the sustainability of indigenous food systems.

Advocacy work ahead

As natural habitats are being lost to plantation expansion, land grabbing and other unsustainable development trends that usurp indigenous lands, access to and availability of wild food sources are declining. Deforestation, ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss create imbalances in the local natural systems, weakening barriers between humans and wildlife and enabling the emergence of zoonotic diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the need for keeping our forests and our wildlife healthy to prevent future transmission of dangerous pathogens.

Despite their intrinsic value, wild foods are excluded from the official food systems measurements and indicators, as the focus of food security has always been on commercial agriculture. Even the Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger which emphasizes sustainable agriculture for food security and improved nutrition, does not recognize wild foods’ substantial contribution to global food security and nutrition.

Emphasizing the value of wild foods is necessary to ensure that our policies support sustainability and conservation of ecosystems and habitats that bear wild foods. Indigenous women possess the skills and knowledge about wild foods’ conservation, harvesting, and preparation according to traditional recipes, and their contribution to food security and nutrition needs to be recognized.

When scientists and policy makers meet for the next Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, they must incorporate traditional food systems and the contribution of indigenous peoples to conservation into the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown us that wild foods and indigenous strategies for forest management are an important piece of the sustainability puzzle, not just for indigenous peoples, but ultimately for saving us and our way of life.

This article was originally published on the SIANI website.

Tanya Conlu is a natural resource manager, a member of the IUCN global volunteer network Sustainable Use and Livelihoods (SULi), and an honorary member of the ICCA Consortium. She has been working with indigenous communities in South and Southeast Asia for over a decade and previously in various environmental projects involving wildlife conservation. An advocate for sustainable living, she is based in the Philippines and is part owner of an online refillery store.