More than 20 delegates across Southeast Asia attended the virtual learning session on Forest Governance and Tenure Rights hosted last February 25 by NTFP-EP Asia, with support from the Green Livelihoods Alliance and the Mekong Regional Land Governance Project.

The event, the first part of a learning series, aimed to give participants an overview of the historical basis and policy origins of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) define its key elements, highlight its benefits, determine its applications in the context of forestry and customary tenure, and identify the existing issues and barriers that hinder its implementation.

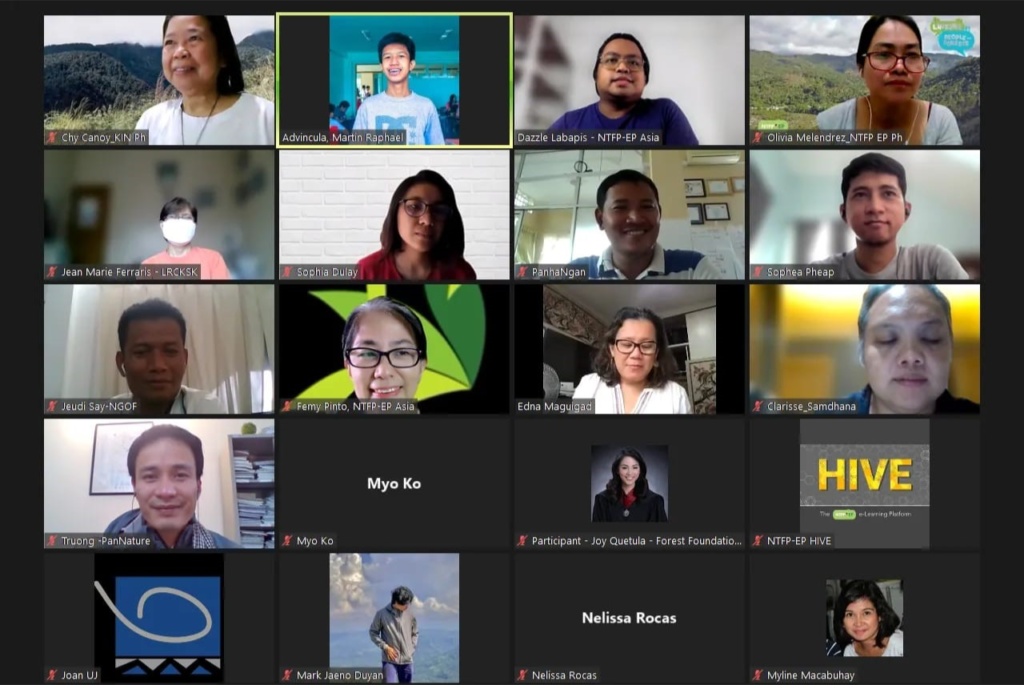

Of the participants, 11 were from the Philippines, four from Myanmar, two from Cambodia, and one delegate each from Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The delegates, with 11 participating women and nine men, represented civil society organizations and indigenous people organizations that compose larger networks such as the CSO Forum in ASEAN, the Green Livelihoods Alliance Regional Collaboration, and the ICCA Consortium Southeast Asia.

“Hopefully learning sessions like these can push us more towards sharpening our strategies as we learn more about the intricacies of these principles,” said Femy Pinto, executive director of NTFP-EP Asia.

Participants of part one of the FPIC and Safeguards learning session

Community’s consent, importance of FPIC

Millions of people, mostly indigenous peoples, depend on forest lands for their livelihood, sustenance, and cultural identity. Indigenous peoples’ control and use of their ancestral lands and waters have been determined by their indigenous knowledge, systems, and practices that have been accumulated through generations.

To help protect the rights and interests of indigenous peoples when it comes to projects that may affect their territories, FPIC should be given by the indigenous community to the parties initiating the project. FPIC is a collective right, a community process, and a defense mechanism for indigenous peoples that help them defend their lands and resources. It is derived from different conventions, policies, and regulations that promote a two-way and human rights-based approach to development.

With FPIC, communities can give or withhold consent to projects that may affect their livelihood, resources, and territories. This also allows them to withdraw their consent at any point in the duration of the project. FPIC is also important as it gives the stakeholders the opportunity to negotiate certain conditions under which the projects are designed, implemented, and monitored.

“Of course, FPIC does not exist in a vacuum. Look at it, not only at the consultation process, but also at the rights of the community to determine their own development,” said Edna Maguigad, NTFP-EP’s regional researcher for customary tenure and FPIC.

Maguigad further discussed how consent plays a role in development and its importance in operationalizing rights-based development. She also linked how traditional occupations of indigenous peoples place itself in modern development and technology. The technology transfer and its application should fit the right need and direction of the development of the community.

“If the proponent has this vague notion that FPIC is a simple consultation, there lies the problem. FPIC should be considered as an important aspect of the operational development,” said Maguigad.

“[FPIC] is not just simple right. It is a right to have land [and] to life,” she added.

Consent given by the community should be recognized based on three standards: free, prior, and informed. Free implies that consent should be given voluntarily without intimidation, coercion, or manipulation. Prior indicates that consent should be sought in advance before starting any activities within the project site. Informed means that the community has a full grasp of the information about the project.

Aside from being an extremely important part of any project initiated in ancestral lands, FPIC is a principle that encourages the best practices when it comes to sustainable development as it encompasses rights, life principles, cultural identities, and traditions of all involved stakeholders.

While consent can be defined differently in various books, guidelines, and protocols, it can also be viewed as a social contract.

“[Consent] is an obligation by one person to another and that kind of agreement can be in various forms,” said Maguigad.

She also listed different ways in which a social contract is formed, such as simple oral agreements or a blood compact witnessed by the community members.

“What is the difference between yes, no, and maybe? Should consent be given only once for all parts of the project? Is it only one time?” asked Maguigad, encouraging the participants to clarify the terms of consent first.

Questions and reflections

Chy Canoy from Kitanglad Integrated NGOs (KIN) from the Philippines shared about the intrusion of companies in the local area. The chemicals from agribusiness can cause harmful effects to the land and cultural structures will also be impacted.

”How would [the local community] fortify their defenses? How to respect their grievances?” Canoy asked.

Maguigad responded that the foundational issue of FPIC application depends on the size of the area which the community has rights over.

“If everything else fails, there should be judicial process and legal framework. It should be an operational right of indigenous peoples in FPIC and customary law,” she answered.

In continuation of the exchange, Sophea Pheap from NGO Forum in Cambodia raised the concern of other countries having difficulty integrating FPIC.

”Which principles should we introduce [to integrate FPIC]?” Pheap asked.

Maguigad expressed her interest and responded by acknowledging that some countries decide against adapting FPIC as it is controversial.

”If at the national level, participation is already relevant, it will evolve. And at your own context, you can define FPIC,” said Maguigad.

As the first part of the FPIC workshop series concluded, participants expressed key takeaways from the event, such as how the principles of FPIC apply to their context along with the correlation to concepts such as customary laws, economic rights, social and cultural development. They have also looked into gaps and violations in FPIC and synthesized that FPIC is a principle, a right, and a process.

The second part of the learning series is tentatively scheduled for April 2022 and will focus on analyzing selected case studies in ASEAN on FPIC, and exchanging knowledge and strategies for policy advocacy.

_____________

Interested parties from the GLA, CSO Forum in ASEAN, and the ICCA Consortium may request a copy of the session recording by contacting info@ntfp.org.

Article written by Sophia Dulay, TRG Intern for NTFP-EP Asia