Article written and published originally by the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact

Under the key theme “Building a Green, Healthy and Resilient Future with Forests”, the fifteenth World Forestry Congress, held from 2 to 6 May 2022 in Korea, provided a platform for around 10,000 participants from all over the world to discuss the fundamental role of forests in the global sustainable development agenda.

Within the conference sub-theme, “Nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation and mitigation and biodiversity”, the side-event “Communities Speak: Indigenous Peoples’ Local Actions and Initiatives are Vital to Implement the Paris Agreement and the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework” was co-organized by the Asian Farmers Association for Sustainable Rural Development (AFA), Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP), and the Non-Timber Forest Products-Exchange Programme (NTFP-EP) on 5 May 2022, as part of their #CommunitiesSpeak advocacy agenda. #CommunitiesSpeak is an advocacy agenda that weaves together the voices and experiences of a network of smallholders, community forest and farm producers and enterprises, Indigenous Peoples, and Local Communities living in forests and forested landscapes.

The hybrid side event, attended by around 60 participants from across the world, opened space to reflect on the essential roles and contributions of Indigenous Peoples to the global fight against climate change and biodiversity loss, as well as to explore advances, challenges and recommendations in relation to Indigenous Peoples’ biodiversity and climate change engagement at different levels, in particular, in relation to the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework and the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Moderated by Lhakpa Nuri Sherpa, Head of the Environment Programme of AIPP, the event featured indigenous speakers from different organizations and communities from Nepal, Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia. While the first three presentations provided the audience with insights on climate and biodiversity action and advocacy from an international, regional and national perspective, this broader focus was complemented by local stories from two Indigenous Women leaders on biodiversity protection and climate change resilience in their communities.

In her presentation “Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP): Opportunity to amplify the stories and initiatives of Indigenous Peoples”, Ms. Pasang Dolma Sherpa, Co-chair of the Facilitative Working Group (FWG) of the LCIPP, and Executive Director of the Center for Indigenous Peoples’ Research & Development (CIPRED), highlighted that Indigenous Peoples, while comprising only around 6% of the global population, safeguard more than 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity, and thus, play a key role in climate protection.

Ms. Sherpa shared that, for the first time in history, the 2022 report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability refers to the recognition of the inherent rights of Indigenous Peoples as integral to successful forest adaptation in many areas. According to the speaker, the recognition and protection of their inherent rights forms the basis for Indigenous Peoples to continue their traditional resource management and thus, to contribute to solutions to current global crises. However, present forest regimes continue to neglect Indigenous Peoples’ rights and values, and fail to recognize their significant contributions to biodiversity protection and climate change mitigation. In particular, the 30x 30 initiative, a plan to conserve 30% of planet’s land and sea areas by 2030, is posing threats to Indigenous Peoples and their traditional livelihoods. Ms. Sherpa stressed that a human rights-based approach is the only solution to ensure sustainable conservation, not only as a necessary means to protect indigenous knowledge systems, and to halt and reverse biodiversity loss and climate change, but also as the most cost-efficient way of conservation.

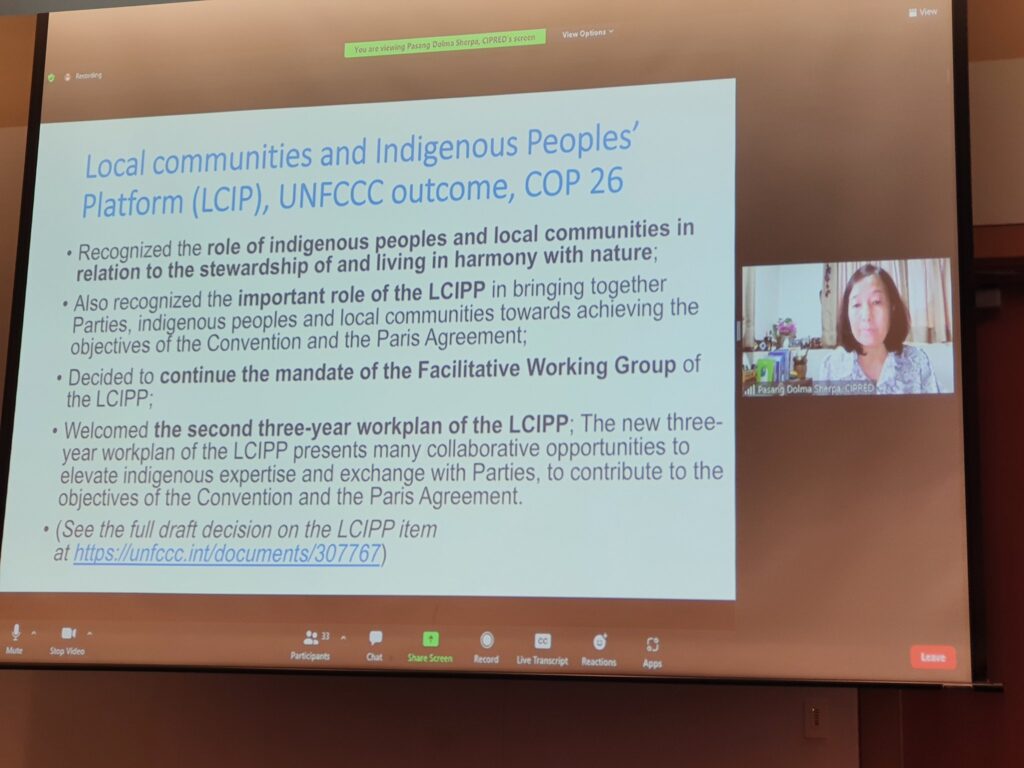

In the second part of her presentation, the speaker shared in-depth insights in Indigenous Peoples’ engagement in global climate change processes. She introduced the work of the FWG, established in 2018, with the objective of further operationalizing the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP), and of facilitating the implementation of its three function of knowledge exchange, capacity building, and the design and implementation of climate policies and actions. She elaborated on the different layers of activities of the FWG within the UNFCCC, including various meetings and dialogues bringing together Indigenous Peoples, Local Communities (IPLC), and state parties, to ensure an equal footing and a holistic approach to climate solutions.

Finally, Ms. Sherpa reflected on the key achievements and opportunities of FWG-LCIPP: the body, with half of its members from Indigenous Peoples’ organizations, has created an unprecedented space for the promotion and recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge, cultural practices and governance systems, successfully ensured the coordination and communication with bodies under and outside the UNFCCC, and adopted a second 3-years work plan at the COP26.

A human rights-based solution is not only for the protection of our knowledge system and cultural values, and contributes to climate change resilience and biodiversity, but it is also the cheapest way of conservation in comparison to the investment by the State Parties on the protection of the national parks and conservation.

Ms. Pasang Dolma Sherpa, Executive Director of CIPRED, Nepal

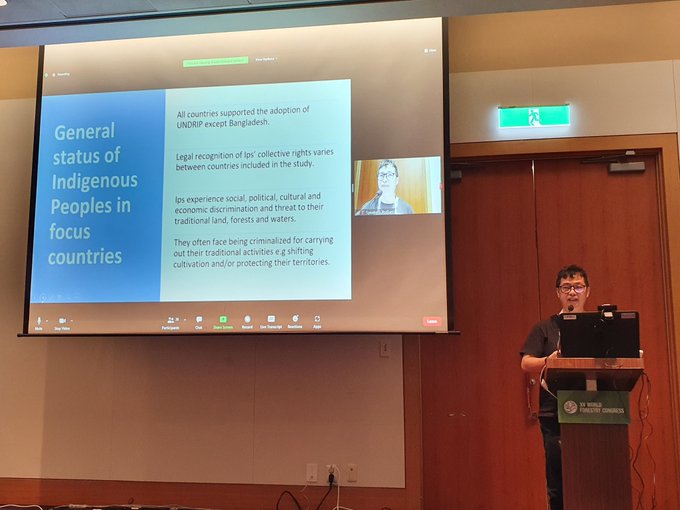

In his presentation on “The Implementation of the Paris Agreement: Regional Overview of Asian Indigenous People” Mr. Kittisak Rattanakrajrangsri, Chairperson of AIPP, discussed how indigenous rights and knowledge are taken into account in Asia, in particular in the context of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) and REDD+. The speaker opened his presentation by giving an overview of the general status of the Indigenous Peoples in 10 countries in Asia – Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. While all countries, except Bangladesh, have adopted the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and UN Human Rights treaties, the legal recognition and implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ collective rights on the ground varies significantly, with some positive examples from the Philippines and Indonesia. The speaker identified common challenges for Indigenous Peoples across the region, in particular, ongoing social, political, cultural and economic discrimination and threats to traditional land, forests and waters. Indigenous communities are also disproportionately impacted by climate change.

Mr. Rattanakrajrangsri underlined the successful advocacy work of Indigenous Peoples in the context of the Paris Agreement and pointed out its most relevant articles for IPLC, as well as government-supported activities on the ground, most importantly, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), REDD+ and the National Adaptation Plans (NAP). Against this backdrop, he introduced a study conducted by AIPP, the United Nations Development Programme (UNPD) and the Forest People Program (FPP) on how the rights, roles and knowledge of IPs are addressed in national-level climate action plans and policies in 10 Asian countries. The analysis revealed that Indigenous Peoples are often invisible as rights holders, knowledge holders and agents of positive change. Mostly, policies fail to make specific reference to Indigenous Peoples, with a few positive exceptions, e.g. Cambodia, Nepal, and the Philippines. With regard to REDD+ policies and activities, the study shows that policies and plans consistently contain language and provisions for Indigenous Peoples and their rights, likely due to the requirements of the Cancun safeguards and other guidelines.

The study also identified concerns of Indigenous Peoples in relation to existing national climate change policy, in particular, the lack of recognition of customary land rights, with some policies even criminalizing traditional practices. Moreover, Indigenous Peoples, continue to lack of broad and effective participation in decision-making processes. The speaker concluded his presentation by stressing the vital contributions of Indigenous Peoples to climate change adaptation and mitigation, through the protection of forest and biodiversity, the maintenance of knowledge on adaptation to harsh climatic conditions, and the provision of examples for food system resilience, e.g. during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“From the study we also found that the climate change policy exclusively fails to address the land tenure insecurity caused by the lack of legal recognition of customary land rights and the related threats to traditional livelihoods faced by Indigenous Peoples. In several instances, the policies even contribute to the criminalization of traditional sustainable practices, by defining them as drivers of deforestation.”

Mr. Kittisak Rattanakrajangsri, Chairperson of AIPP

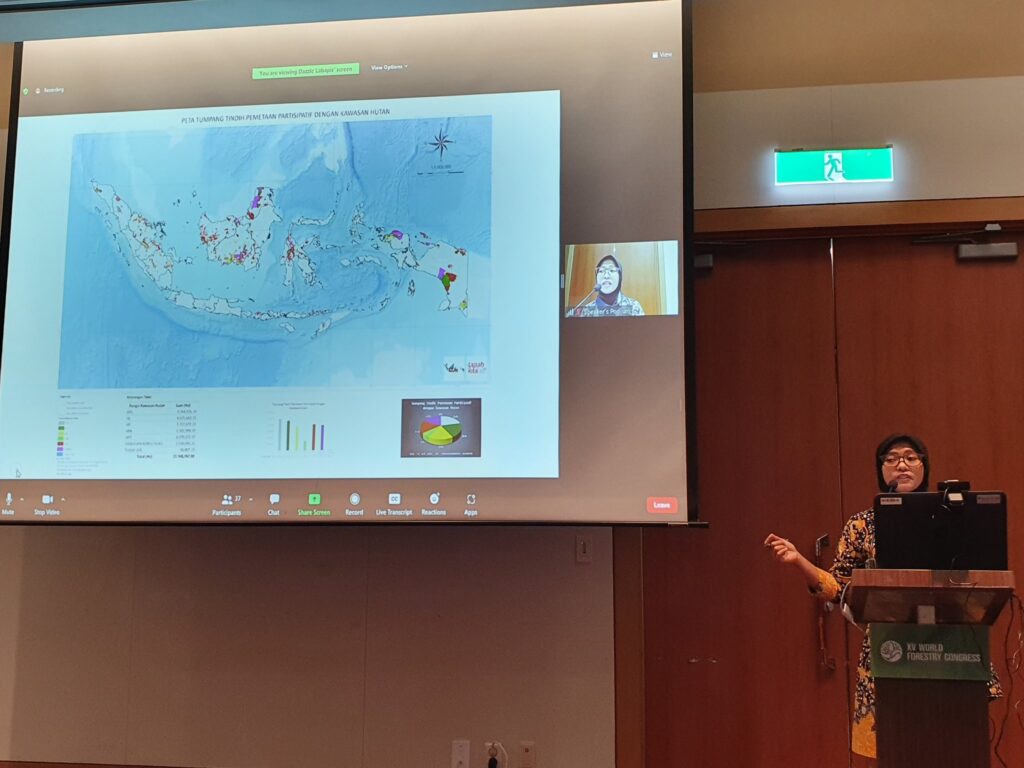

Ms. Dewi Sutejo, Vice National Coordinator of the Indonesia Community Mapping Network JKPP, and Member of the Regional Council of ICCA SEA, and Mr. Giovanni Reyes, President of the Philippine ICCA Consortium and Member of the Indigenous Peoples’ Advisory Group of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), gave a joint presentation on “Why Human Rights Based Approach Essential for Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework?”.

In the first part of the talk, Ms. Sutejo presented an overview of the work and dedication of the ICCA Consortium to promoting the recognition of Indigenous Communities Conserved Areas (ICCAS) and to scaling up a human rights-based approach in the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, particularly in light of the planned 30×30 initiative. The speaker showed that around half of all recorded agrarian conflicts in Indonesia in the first quarter of 2022 occurred in protected areas and conservations forests, many of them in customary areas in national parks. In this context, she stressed the lack of recognition of IPLC territories by governments in Southeast Asia, with only 8.7% of them being legally recognized across the region. To address these challenges, the rights-based approach of the ICCA Consortium in Southeast Asia focuses on three key areas: 1. the documentation of the land use of IPLC in order to secure rights over lands and resources, and to FPIC; 2. the sustenance of livelihoods, including the protection of IPLC natural resource management, food systems, and governing institutions, and 3. environmental protection, including the protection of IPLCs in the frontline of the defense of forests. Ms. Sujeto highlighted the lack of the recognition of ICCAs in Southeast Asia at the example of Indonesia where the Working Group ICCA has registered 104 spots of ICCA, but only 25 ICCA are legally recognized by the government.

“22 million hectares in Indonesia have been mapped by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, out of which 17 million are actually under IPs territory (…) From the total 17 million, (…) only like 2 million hectares have already been recognized by the government, so it’s still small portion, there is a lack recognition by the government of the Indigenous People and Local Communities’ area. So we still have long work and homework with the working group ICCA, to ensuring the documentation of ICCAs.”fining them as drivers of deforestation.”

Ms. Dewi Sutejo, Vice National Coordinator of the Indonesia Community Mapping Network JKPP, Indonesia

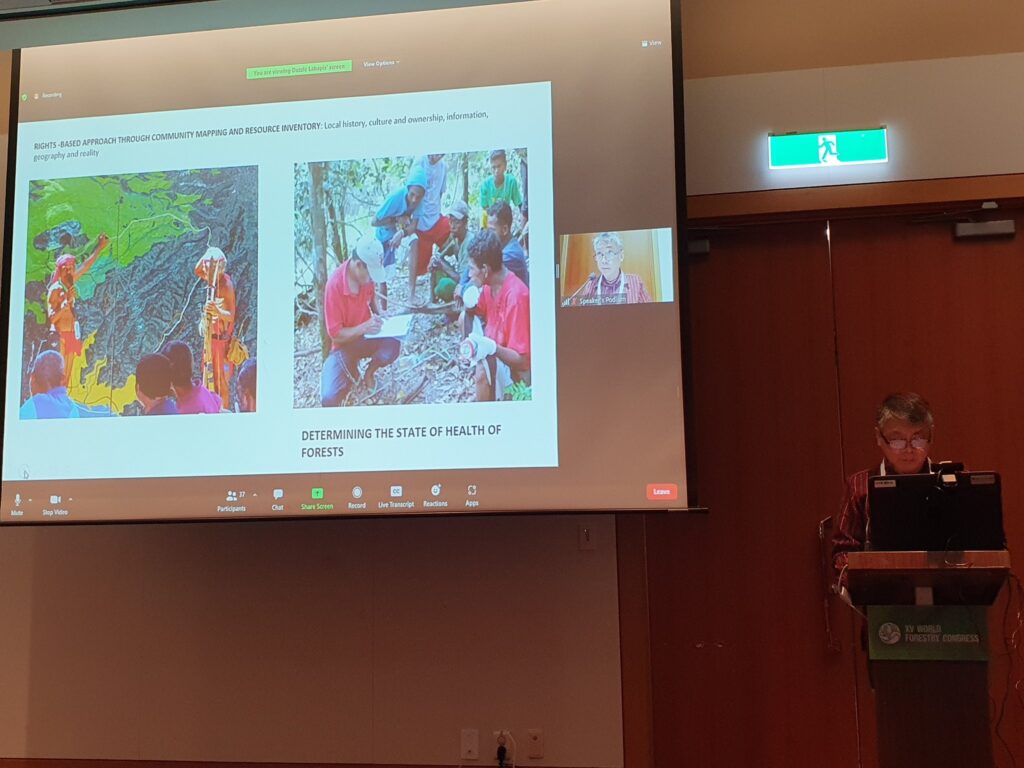

In the second part of the joint presentation, Mr. Reyes described how, in the documentation process, the rich traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples is translated into maps, which are then used by Indigenous Communities to enhance their positions in negotiations. To ensure the application of a rights -based approach, Mr. Reyes emphasized the need to strengthen the merging of indigenous knowledge with scientific methods. He described that an analysis of mapping findings in 10 ICCA Pilot sites in the Philippines by the World Resources Institute showed that these 10 sites are able to hold at least 10.5 million tons of carbon, an amount equivalent to the emissions of 7 million cars annually. Using this example, he stressed that the enormous contributions of Indigenous Peoples to climate change mitigation remain largely invisible and neglected. The speaker recommended, inter alia, that the post 2020 GBF negotiations need to address Indigenous Peoples’ rights to land and resources, including FPIC, consistent with internationally recognized human rights standards, and that strong accountability mechanisms and access to justice need to be established. Mr. Reyes concluded that there is no future for the world’s forest without Indigenous Peoples standing.

“Indigenous Peoples’ contribution in conserving 80% of the world’s biodiversity areas is unparalleled. Ensuring a rights-based approach will scale up mainstream forestry and will prevent the destruction of forests. Support for Indigenous Peoples means support for forests, disrespect for their rights, do it at your own peril.”

Mr. Giovanni Reyes, President of the Philippine ICCA Consortium

The remaining two presentations featured stories from the ground by Indigenous Women leaders from Thailand and the Philippines.

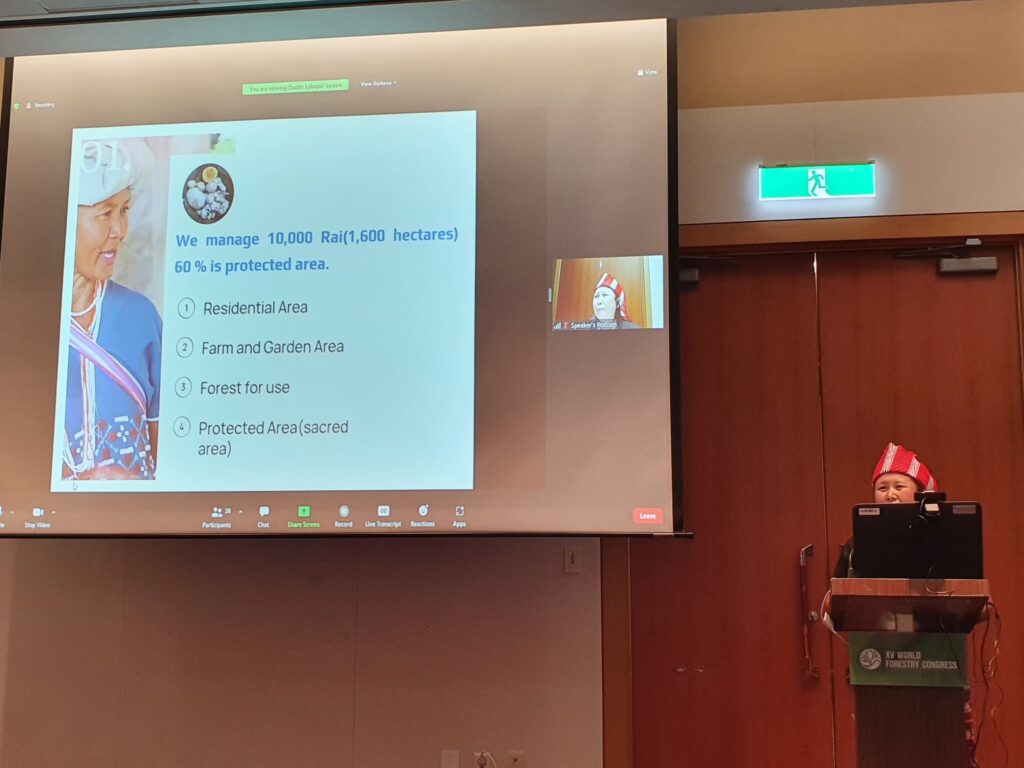

Ms. Nor-Aeri Thungmueangthong, Chief of the Pgaz K’Nyau community Huay E-Khang Village, Thailand, started her powerful presentation “Indigenous Women Leadership on Climate and Biodiversity Protection” by emphasizing the crucial role of Indigenous Women as knowledge holders and agents of change in biodiversity conservation and climate action. She described the women’s deep respect for the forest as the foundation of all life and as dwelling place of spiritual beings. Ms. Nor-Aeri depicted the customary land management of her community, which is based on traditional beliefs, knowledge and modern scientific approaches, such as community mapping. The community’s management system, which also includes protected areas, mirrors the deep relationship between humans, nature, and the supernatural. An example is the umbilical cord ceremony De Po Htoo in which the villagers tie a bamboo container with the umbilical cord of a newborn to a tree, symbolizing that the spirit of this person is living in this tree, which cannot be cut. Traditional knowledge, passed down between generations, has ensured the conservation and protection of the forest for the more than 500 years. Ms. Nor-Aeri shared how the Indigenous Women in Huay E-Khang have revived their Indigenous Women’s forest, a learning space and source of health and well-being, food and income for the women, even in time of crisis, like the Covid-19 pandemic. She presented various community initiatives on forest conservation and maintenance, including forest monitoring, community mapping, fire management practices, and the creation of a community fund for forest protection.

The presenter pointed out that women as knowledge holders play a key role in combatting climate change, in particular, in terms of the conservation of native seeds, the majority of which are derived from rotational farming, a practice often criminalized as ecologically harmful. As owners of the seed, Indigenous Communities are able to retain independence from commercial seed suppliers and thus, food sovereignty. The speaker stressed that the recognition of land rights is essential to ensure the transmission of Indigenous Knowledge which is crucial to tackle the twin crises of biodiversity loss and climate change.

“Indigenous Women are playing a crucial role in protecting native seeds and (…) we need to pass this knowledge on to future generations. But this knowledge cannot be passed down or continued if there is no recognition of land rights. To recognize our rights to land is very crucial to continue our practices and to contribute to the climate change and the global framework of biodiversity, with women at the center of it.”

Ms. Nor-Aeri Thungmueangthong, Chief of Huay Ek Khang Village, Northern Thailand

Ms. Conchita Calzado, President of Kababaihang Dumagat Ng Sierra Madre (K-GAT), Philippines, introduced the work of K-GAT, a startup agricultural cooperative led by Dugamat women in the Philippines. K-Gat’s key aims, the protection of the environment and of indigenous culture, guide the project activities of the federation, e.g. for women, the production of vegetables, fruit crops and handicraft. Farming is done in a sustainable way, based on traditional practices and harvesting rules that ensure the long-term sustainability of natural resources.

The speaker highlighted challenges facing the Indigenous Women, in particular, the improper implementation of government policies, e.g. related to FPIC. In many parts of the country, environmentally destructive projects are prioritized by the government, such as dam construction, mining, or large-scale tourism projects. The Dugamat women have been actively engaging in dialogues with local officials, government agencies and private companies in order to push for their rights to ownership and possession of their ancestral domains. Even though the Indigenous Community has developed an Ancestral Domains Sustainable Development and Protection Plan (ADSPP), it remains unrecognized by the National Commission of Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) and local government units. Another key challenge for the Indigenous Women members of K-Gat is the indigenous political structure of their group. Although traditionally, women do not engage in governance and decision-making processes, the Dugamat women continue to assert their rights, and to make their voices heard.

“We believe that as Indigenous Peoples, we cannot be separated from our ancestral land and environment because it forms part of our identity. We cannot be called Indigenous Peoples if we are outside our indigenous land, and if we are far from our environment which we are born into. This is why we have this burning desire to protect our land, especially the forest.”

Ms. Conchita Calzado, President of Kababaihang Dumagat Ng Sierra Madre (K-GAT), Philippines

While each presenter offered unique insights into Indigenous Peoples’ actions and initiatives at different levels, some common messages emerged across the diversity of voices: All speakers stressed that Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge, values, customary laws and governance systems fundamentally contribute to biodiversity protection, climate change mitigation and adaptation. At the same time, their huge contributions, their customary land tenure and land rights remain inadequately recognized by governments at national and local levels. Although there is an increased presence and influence of IPLCs over global climate negotiations, with unprecedented space opening up for dialogues between governments and IPLCs, the latter continue to lack of broad and effective participation and equitable representation in the decision-making spaces of global environmental governance. Accordingly, it was echoed across the contributors that only a human-rights based approach to conservation, which fully recognizes and respects the knowledge and rights of Indigenous Peoples, particularly their rights to land territories and resources, can enable the guardians of the world’s ecosystems to continue their customary governance and institutions which form the foundation of their sustainable resource management, and which offer solutions to the intertwined global biodiversity and climate crises.

For more information, please contact the following members of Environment Programme of AIPP:

- Lakpa Nuri Sherpa, Environment Programme Coordinator at nuri@aippnet.org

- Pirawan Wongnithisathaporn, Environment Programme Officer at pirawan@aippnet.org

- Prem Singh Tharu, Environment Programme Officer at prem@aippnet.org