KOTAGIRI, India – The Non-Timber Forest Products – Exchange Programme (NTFP-EP) held their regional meeting in Keystone in the beginning of January. Partner organisations came from Laos, Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and India came for the 3-day meeting, the last day of which coincided with the Wild Foods Festival at Keystone. Femy Pinto, Executive-Director, NTFP-EP Asia, said the Network started thinking about wild foods and the link to the community’s health and wellbeing about 7-8 years ago. This meeting, on the theme of “Coming Home to the Forests for Food”, had 20 participants from five countries coming together to discuss the close links between indigenous people, their heritage of forest foods, and how it directly links human and environmental wellbeing. The meeting did indeed leave everyone involved with plenty of food for thought. Femy also spoke on the significance of the logo. The Penan are one of the last remaining hunter-gathers tribes in Malaysia and they are a small population. The logo shows a Penan man using his blowpipe. This stands for tradition and way of life in the forest and shows how NTFP-EP identifies itself with the community.

Prof. Ramon A. Razal, Trustee – NTFP-EP, spoke on the importance and linkages of wild foods to the overall NTFP scenario. He spoke about what characterises forest foods and also presented reports of nutrient compositions on some forest foods such as pako (Diplazium esculentum) and bignay (Antidesma bunius) that are commonly used by indigenous communities in Philippines. He discussed statistics that showed the greater the anthropogenic pressure on forests, the less healthy the indigenous population is.

Forest foods have a special place in the lives of indigenous people. There are greens, fruits, staples, tubers, bulbs, shoots, mushrooms, and blossoms that yield spices, beverages and oils. The communities also collect animal products like honey, fish, snails, crabs, bushmeat, birds and bird eggs. In Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia alone, there are more than more than 50-60 plant families that are common forest foods prepared in many ways. For example, Bignay (Antidesma bunius) fruit can be eaten raw or made into jams and jellies or a refreshing drink, while the leaves are used to flavor fish and meat stews, vinegar, and salads. The participants concurred that is the need for studies on nutritional values and toxicology of wild foods and that forest dwellers are blessed with the traditional knowledge of what to eat, how to eat and when to eat.

Indigenous communities have the traditional knowledge that tells them how to collect and process wild foods safely.

Madhu Ramnath presented an overview of wild foods and the origins of cultivated food. As man settled into farming, wild strains of many plants, eg maize and peanuts, disappeared. Farming increased and farmers shifted to sunlight demanding plants, more and more forest land was cleared and indigenous people wound up working on these farms. Lack of time combined with easy availability of subsidised rations from Public Distribution System had them venturing less and less into the forest to gather seasonal fruits and other wild food which offered essential nutrients. Over the years, this has resulted in reduced health in indigenous people as many communities have themselves observed.

Divya Devarajan, District Collector, spoke on the link between governance and wild food in trying to find answers to the question of why indigenous people are having to relearn the use of forest foods. Divya spoke of processes working in parallel that were bringing about this change, the first being the residential form of education that takes the tribal children away from their families and their culture. Along with the displacement of the child during its formative years from its community, comes with the dichotomy between traditional knowledge and current school curriculum, which is designed keeping the urban population in mind and is totally out of touch with tribal children’s realities. At the end of formal schooling, the child has grown up to be urbanized but less knowledgeable person.

With more and more forest land being ‘developed’ (converted) or ‘protected’ (restricted) , the forest dweller has to relocate to nearby towns or city to be able to provide for the family, The Forests Rights Act in India came up assuring long-time forest dwellers the right to residence as well as rights to collect NTFPs for subsistence and livelihood, but the processes involved and tedious and confusing. Coupled with the lack of access to forests comes the convenience of the Public Distribution System where wheat, rice, and sugar are made available to the community at subsidized rates. When the women have to spend so much time and effort to prepare millets and forage for wild foods, as well as take care of livestock and small plots of crops (jobs that earlier were the man’s responsibility), they prefer to accept what is supplied through the PDS, leading to a gradual shift in diet.

Ms Bhanumathi Kalluri’s presentation on “Gender Perspective to Wild Food” made the participants think about what the distance from wild foods has meant to the indigenous woman. Bhanumathi is Director of Dhaatri, a resource centre for women and children’s rights based in Andhra Pradesh. The collection of wild food was the woman’s area of expertise and also a group activity which gave them a change from their daily routine. When the families gave up their traditional houses and shifted to government-funded cluster housing, the woman lost her exclusive physical space where she maintained stocks of grains and wild foods. Canned entertainment from the television has eaten into the time that the women would spend in each other’s company, be it gathering wild foods, pounding millet, singing songs or telling stories – space for imagination has reduced.

Current school curriculum, even in tribal areas, is tailored to urban sensibilities. Indigenous festivals and traditions have yet to find a place.

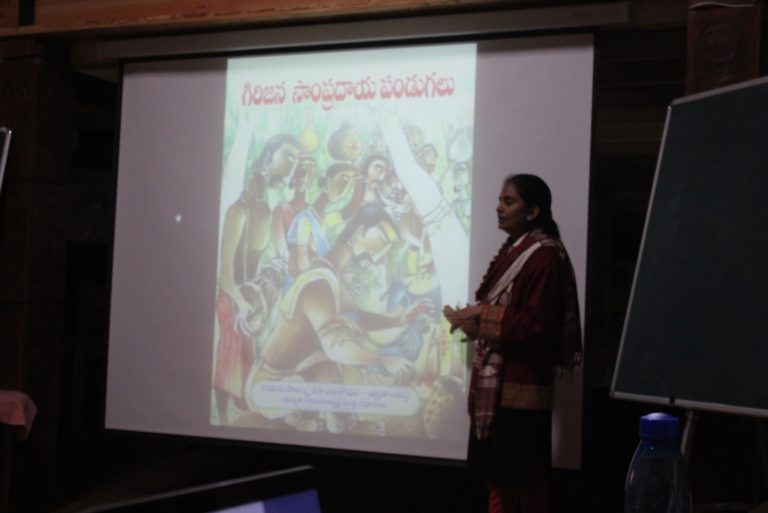

Divya spoke about changes to the system that might help resolve some of these problems, some of which has already started to be implemented. To address the changing diet of indigenous people in Andhra Pradesh and Telengana, decentralization of the PDS system has begun in an effort to ensure that local produce is distributed via the system maintaining the traditional healthy diet of the people. Divya also gave other suggestions such as a minimum support price for millets which assures the farmer some insulation from adverse market conditions, introducing traditional foods into the mid-day meal programme in schools. Elaborating on the lack of connect between generations, Divya spoke of redesigning the curriculum to include local practices, traditions, festivals, etc. Acting on this, she has already created a compilation of 12 indigenous festivals presented in the story form which is being introduced into the school curriculum in her district. She hopes to be able to synchronize school vacations to major tribal festivals to enable the children to reconnect to their heritage, hire teachers from the community to ensure that the indigenous language is kept alive, encourage tribal elders to give a small part of their time every week to pass on a skill set to the next generation. All said, this was an extremely thought-provoking session by one who has been closely observing and analysing situations in the districts under her jurisdiction.

While on the outside, it may seem that going back to how we used to live is perhaps the answer, but that would not be feasible. It is more necessary that we develop plans to instil pride in one’s culture that is real and sustainable and be able to use technology to help us down that road. The scale of a landscape solution is intimidating, but we could consider decentralized solutions and create small islands of successes that can reach out and spread the change.

Presentations from the other partners spoke about small initiatives aimed at keeping interest in wild foods and traditional seeds alive. Amar Kumar Gouda from Regional Cooperation Development Centre (RCDC), Odisha, has found success in their “Bihan Mita” (Friends for Seeds) and “Bihana Maa” (Seed Bank) programmes. The former programme involves exchange of indigenous seed species between farmers and the latter is seed conservation at the household level. Such initiatives are crucial for protecting native wild species from vanishing. Speaking to the forest dwelling communities in Jharkhand, Paryavaran Chetna Kendra has listed at least 40 wild foods that have become rare or have disappeared from the forests.

Keystone presented on uncultivated or wild foods in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve which is home to more than 30 distinct indigenous communities, each of which has its own understanding of wild foods collection and preparation. Shiny and Ramachandran spoke about the Conservation Education school programmes on wild foods, Village Elder Programme that facilitates transfer of traditional knowledge, health awareness programmes, developing nurseries of wild foods and documenting the types and uses of wild foods and traditional practices associated with it.

Pratim, “Is the past the future?”

As the discussions progressed on how each NTFP-EP partner can take their work and look at linkages around wild foods, a way ahead gradually started to emerge starting with creating of a database on wild foods combining traditional knowledge regarding collection and use with scientific data on nutritional value, availing opportunities provided by legislations for increased access to forests and motivating local governance institutions to follow through with processes, engaging with community elders to conserve traditional knowledge and use technology to make traditional wild foods easy to process. We are witnessing a re-emergence of wild foods and a new consciousness about wisdom of days long gone by. Although some of this consciousness has respect for the traditional knowledge and indigenous culture, the application may not be holistic because of herd mentality and incomplete knowledge. In all well-meaning initiatives there is both the pro and the con. The government programmes aiming to ‘better’ the indigenous peoples’ lives do not take into account the community’s definition of ‘better’. The challenge, as always, is to find the balance between what can be conserved as is and how much has to be allowed to adapt to changing seasons and work to maintain that balance. As Madhu said, “Progress is inexorable. We cannot turn back the clock. All we can do is go back to a simple honest framework and stop there.”

Original article posted on Keystone-Foundation.org