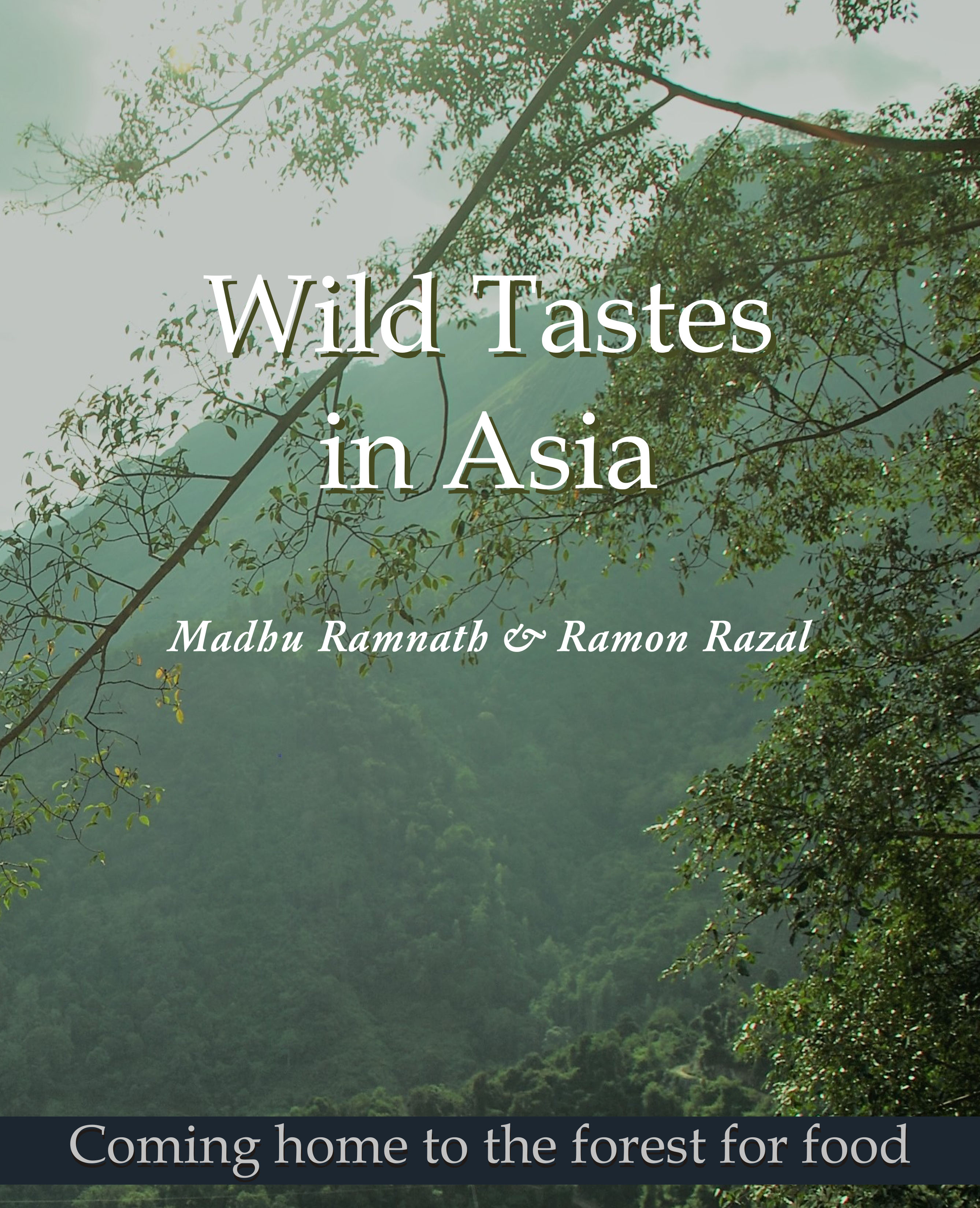

Written by Madhu Ramnath and Ramon Razal, Wild Tastes in Asia gives us a glimpse into the array of factors that go into the collection of food in the wild. Apart from skills, these factors include the knowledge to identify species, the spaces and times when particular foods become available, the resources necessary to collect certain foods (like traps and diggers), the norms involved in gathering and sharing food, and the traditions that ensure sustainable harvests of resources.

How to order a copy

Interested in a copy of Wild Tastes in Asia? Contact us at info@ntfp.org so we can arrange a delivery to you or your organization. Certain partner organizations and institutions are entitled to a free copy of the book as well.

We are currently working on making the book available in e-commerce platforms and book shops. We will announce soon when this is available.

Reviews

Here’s what the experts have to say about Wild Tastes in Asia:

Dr. Jeremy Ironside

NTFP-EP trustee and McKnight Foundation consultant, with interest in sustainable agriculture and communal land and natural resource management

This book represents a truly important effort to understand the access to and use of wild foods in South and Southeast Asia. One key lesson from it is the significant variety of foods which forest peoples have relied on for centuries. This stands in significant contrast to modern diets which are based on a limited number of industrially produced staple foods. It also confirms recent research which shows the importance of food diversity for gut and general health.

As an Agta elder points out in the book “Medicinal plants are not the reason why the Agta are healthy. We get our strength from the food we eat, particularly the food which we learned to eat from our ancestors.” A further important lesson from this book is the way communities manage their local areas for sustainable food production. This includes the replanting of yams after some have been dug out, bans on collecting bamboo shoots at certain times of the year, festivals before opening the collection of certain fruits, the maintenance of sacred areas, etc. The French have a term called ‘terroir’ which describes the combination of the soil, climate, topography, etc. and how these are managed to create a particular wine, coffee, tea, etc. Perhaps in the forest/wild food context this concept of terroir can help to illustrate the connections local people build with their territories through their belief systems and then manage them for a range of foods using their traditional knowledge.

Madhu and Ramon’s book gives us a small opening into the extreme complexity of these traditional management practices and the way territories are sustainably managed for peoples’ livelihoods and for preserving diversity. Unfortunately the book also points out the dangers which we now face both from the loss of forest areas and also the loss of the accumulated knowledge which has enabled their sustainable management. This book is therefore more than anything a wake up call both to protect forest areas and also the knowledge of the people who call these forests their home.

Dr. Denise Margaret Matias

Research Scientist at the Institute for Social-Ecological Research (ISOE) Germany and Fellow of the Sustainable Use Assessment of IPBES

I first read the Wild Tastes in Asia book during its launch at the quadrennial wild honey bee conference “Madhu Duniya.” During this online launch in the time of COVID-19, discussing wild foods becomes even more important as wildlife consumption bans are contemplated and/or enacted by governments. The book reminds us that wild foods in Asia do not only contribute to food security of indigenous peoples but are also repositories of knowledge and culture. This is a good reference book for those who are wishing to learn more about opportunities as well as threats from wild foods of indigenous peoples in Asia. Lastly, this book will also be helpful to the ongoing thematic assessment on sustainable use of wildlife of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

Giovanni Reyes

Sagada-born Kankana-ey, Western Mountain Province, Cordillera Administrative Region. President, Philippine ICCA Consortium (BUKLURAN, Inc.) Philippines. Member, Indigenous Peoples Advisory Group-Global Environment Facility, Washington DC. Council Member, The ICCA Consortium, Geneva, Switzerland

The book Wild Tastes in Asia by Madu Ramnath and Ramon Razal is not just about “coming home to the forest for food.” It’s a living story enriched by a variety of ‘food treats’ mainly from indigenous peoples’ traditional territories others call ‘gene banks.’ The 181-paged book wriggles us through from plants, to fruit trees to root crops, meat and fish, their means of planting, production, time of harvest, food gathering and cooking, or slow food, so to speak. One is satisfied at the end – because it shares understanding about indigenous peoples and the link between food, food security and food sovereignty with the control and use of land and water bodies determined largely by their indigenous knowledge, systems and practices.

Such link, for Indigenous peoples’ communities in the Cordillera Region of Northern Luzon of the Philippines where I come from, for example, have no worries about food shortage in crisis situations. This link has been sharpened when age-old practices of food storage systems like “Agamangs” or rice granary and local practices of lockdowns like “ubaya” or “tengao” were reactivated in the face of a global lockdown triggered by Covid19. This practice tells us, in a manner of speaking, that today’s consumption is last year’s harvest. I myself experienced eating rice kept for 40 years in an agamang! An agamang exists because of the idea that no Igorot should suffer from hunger. For a race that carved the Cordillera mountains into rice terraces and creating colossal food stairways above the landscapes – an unparalleled feat, that when stretched end to end, these rice paddies could reach half the globe’s circumference – to go hungry whether under pandemic or war is considered “inayan” or taboo. This brings us to the idea of “food security” which to many has come to mean “vulnerability to lack of food supply.” It connotes “inevitable hunger” due to problem of production and distribution of crops triggered by “land conversion.” For others, it has come to mean non-accessibility of food either because of “non-availability” or “affordability.” All these, in the face of takeover of markets through trade in goods and services that tells us what to buy, eat and consume because it’s good for us. But among front-liners in defense of environment, health and nutrition, these occurrences are largely a combination of market-led ‘solutions’ and state-implemented maladaptation. For indigenous peoples, food production and distribution is about food sovereignty. From time immemorial, we have learned to equate food systems with LIFE-PRINCIPLES, that is to say – life is not only satisfactory when food is available, adequate, accessible and acceptable to indigenous peoples, but rather, when we have access to and control over our land and resources.

In the Philippines, some 20-25 millions Filipinos including lowland farmers living adjacent to ancestral domains benefit from ecological services like water. Since rice production is dependent on water supply, threats to indigenous peoples’ lands and resources means threats to the country’s food sovereignty.

I recommend translation of the book in languages understandable to indigenous peoples, and thrust the same for official adoption in the mainstream of agriculture policy. We can’t be “new normal” with the “old normal” market-led state-implemented maladaptation practices.

Maria Rydlund

SSNC Senior Policy Advisor Tropical Forest at SSNC, ecologist, doing policy work a rights based approach acknowledging the role of indigenous peoples and local communities; in partnership with civil society organisations in tropical countries, based in Sweden.

Wild Tastes in Asia beautifully and timely reminds the

reader about what should always be the way we see forests – the richness they

provide in terms varieties, food, culture and raw material for a number of

non-timber products. The role of forests as a place for food gathering is

seldom even brought on the table when value and governance are being discussed.

The fact that many people see their forest as a pantry has been neglected.

Instead, the value of forests tends to be measured in terms of the number of

cubic meters.

The book guides the reader through the history of

forest in the six countries covered (Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia,

Philippines, Vietnam and India), the value for indigenous peoples and feeds the

curiousness for wild food well with a good mix of colour photos and informative

text, also with the scientific names. The latter adds yet another value to the

book and still it stays very readable and interesting for any reader, no matter

level of knowledge.

The intricate systems of norms and means is a section

that deepens the way forest are managed and utilised by indigenous people. The

cultural value, customs and rituals are vibrant also in forests as well as in

other places but maybe less known by many. The farmer’s almanac is more often

referred to maybe and the book covers many interesting aspects that deepen the

understanding of the values of forest. It also raises questions such as if

knowledge will continue to be transferred to youth if interest is declining, a

relevant question of course. Ways to revoke interest and knowledge for

something that constitutes the most optimal food web and food sovereignty has

certainly been alerted given the current situation with pandemics. The future

of forests lay in our hands, but our survival depends on environment and

healthy environment. The way the subtitle puts it – Coming home to the

forest for food – might capture it in the very best way.

It is a very nice piece of work and a unique theme that should be widely shared with many. After reading the book one will never walk through a patch of forest without looking for edible plants, berries, mushrooms – for food – no matter wherever in the world that forest is!

Elena Aniere

South East Asia and Pacific Regional Director of Slow Food, a global network of local communities founded in 1989 to prevent the disappearance of local food cultures and traditions and counteract the rise of fast food culture. Since its founding, Slow Food has grown into a global movement involving millions of people in over 160 countries, working to ensure that everyone has access to good, clean and fair food.

This book, Wild Taste in Asia, could not be released at a more appropriate time than now, during a global COVID 19 pandemic, where food is at the centre of our conversations. Whether it be the question of food safety, food insecurity, food choices, food waste, food distribution and/or food as medicine, like the pandemic, people globally are being affected with these food issues.

This book highlights the symbotic

relationships between the indigenous people, wild foods and the cultural identity

in 6 Asian countries: Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, India, Cambodia and

Malaysia. Where the forest is home, free to gather or forage wild foods, recognized

to contribute to diet and food security through enhancing the availability of

local, diverse, and nonmarket food sources. Thus wild foods are linked to diet,

food security, and cultural identity.

Wild Tastes of Asia is a rich and valuable

resource, identifying wild foods that have been a source for nutrition and medicinal

purposes for the repsective indigenous communities and highlights the

commonalities and difference in usage of the same plants.

It is with

thanks to the NTFP Exchange Programme, which has a presence in these countries,

that has now begun to concern itself with the health and nutrition of the

indigenous peoples that it works amongst, and empowering the voices and

capacity of women not only as care givers but also as key culture bearers and

knowledge masters in their communities.

As we strive to regain a balance in our food,

our planet and our future, this book is a great resource to understand how we

can learn from indigenous cultures to be as one with nature, as she provides

all that we need!